One

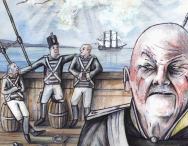

mild Wednesday in February 1797 the last invasion of Britain began.

Round the corner from St David's Head four ships (flying English colours)

hove into the rocky bay of Fishguard.

Yet

although the 1400 soldiers were dressed in British uniforms these were dyed

a mottled black. In fact, half the men had joined the voyage straight from

prisons in France, and several of them still wore wrist- and ankle-irons.

Even the regular grenadiers seemed the worst that the nation could supply.

The

men spoke only French and called themselves La Legion Noire (the Black Legion).

Three Irishmen among the officers were interpreters between them and their

elderly commander, who spoke only a kind of English - he was an Irish-American

named Colonel Tate.

The

plans of the generals back in France had been simple: they thought many

countryfolk in the British Isles would sympathise with the recent French

Revolution and would join the invading army in marching against their own

government.

It

was a surprise, therefore, when from a fort on the harbour members of the

Welsh homeguard, under Lieutenant Colonel Knox, defended the Island of Britain.

The

Fishguard Fencibles scared off the enemy with blank shot from their eight

cannon since they daren't waste their ammunition - all 3 rounds of it.

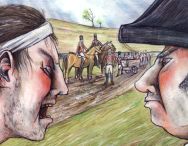

On

Thursday morning Knox received orders to retreat inland to Haverford West.

Along the way he bumped into Baron Cawdor, who was advancing on the coast

with more volunteers, pulling two guns in farm-carts.

Briefly,

the invasion was forgotten. Cawdor and Knox argued over who should be in

command. Eventually, Lord Cawdor took charge, and their combined units hurried

on to Fishguard.

By

this time, the wealthier classes were fleeing the other way. But Lord Cawdor

exhorted them to join him, and many did, together with the local peasantry.

The

army was now well-equipped and would terrify any invader: as well as cannon,

pistols and sabres they carried mattocks and spades, pitchforks, billhooks

and straightened scythes.

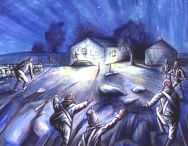

Meanwhile,

the Frenchmen had landed nearby at Carregwastad Point. By moonlight they

had scaled the high cliffs and seized Trehowel Farm as Colonel Tate's headquarters.

Out at sea their frigates left for France.

The

invaders had been well supplied with weapons, gunpowder and hand grenades

but they'd brought no horses and little food or drink. During Thursday they

raided the nearest farms, chasing after sheep and poultry and cooking them

over camp-fires.

In

addition, they found home-brewed beer and plenty of port-wine: this had

been salvaged by the locals from a Portuguese trader recently wrecked off-shore.

Soon the whole Black Legion, except for the Colonel, were merrily drunk.

One befuddled grenadier thought he heard the clicking of a musket - and

had enough fighting spirit inside him to kill the ticking grandfather clock.

The

Welsh, of course, fought back: one Frenchman was tipped down a well; another

stunned with a chair-leg.

Lead

from the roof of St David's Cathedral (with permission from the Dean) was

stripped for bullets. These were given to the countryfolk (men and women)

who set off to the aid of Fishguard.

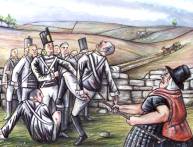

One

heroine was Jemima Nicholas, a cobbler by trade and especially brawny. Jemima

discovered 12 Frenchmen in a field. Wielding a pitchfork, she rounded them

up on her own and marched her prisoners to the local jail.

By

Thursday evening Colonel Tate had had enough of his rabble army. The men

were either asleep, drunk or mutinous. His headquarters were a mess: no

food remained; window frames had been smashed up for firewood; and mattresses

cut up for clothing, their feathers drifting around the farmhouse.

What's

more, his officers reported red-coated soldiers slipping through the countryside.

Clearly, the Black Legion was outnumbered. It was time to surrender.

On

Friday morning Tate assembled his men on Goodwick Sands to give up their

weapons. Still hungry and hung-over, the French troops marched down to the

beach to the beat of their drums.

Lord

Cawdor surrounded them on the hills above. By this time the ranks had been

swelled by hordes of Welshwomen. To those penned on the beach below, their

red flannel shawls and tall black hats resembled British uniforms.

Colonel

Tate realised his mistake: the extra soldiers seen by his officers had been

the women in traditional dress, and the opposing army wasn't so big after

all.

But

it was too late now: on Friday afternoon he signed a note of surrender.

Two days after it began, the last invasion of Britain was over.

*

THE END *